Pakistan — Joy of Life

We reached Khunjerab Pass in the afternoon and directly crossed into Pakistan as all exit formalities had been completed in Tashgurkan.

Directly at the border pass is an ATM – apparently it’s mostly used by border guards.

The Pakistani immigration point in Sost was still 80 kilometer away but we stopped near the border to enjoy the fresh air and watch Yaks. Everybody visibly relaxed and smiled again after the permanent tension you feel in China.

Friendly and professional entry procedure in Sost, then we found a place to sleep. In the last daylight hour I went for a walk and realized quickly the main difference after crossing the border: Pakistanis are full of joy of life.

Joy of life – how would you rate the average joy of life you feel in your current life on a scale from 1 to 10?

What would it for you take to increase that number?

Given your force to co-create your reality in your consciousness, I’m sure that you can increase the average joy of life you are feeling despite all the hardship you experience on your path – it’s a choice.

I got up early and went for a sunrise walk enjoying the mountain scenery – Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region is home to about fifty 7,000 peaks and five 8,000 peaks (border interpretations differ among all Himalaya countries).

A sign from an NGO caught my attention. According to their website their mission is:

“To protect environment at local, national and global level to implement [the UN’s] Agenda21, through advocacy, research, non-political, non-religious and non-racial approach.”

Cool!

I got some rotis, tomatoes and eggs and cooked a large breakfast together with the others.

We relaxed and slowly started cycling around noon – when you are in a beautiful place there is no need to rush.

We passed small mountain villages in beautiful settings – the locals we met along the road were warm, welcoming, and seemed truly happy to meet us.

We followed the Hunza river which forms in this area from merging glacier meltwater streams. Downstream it flows in the Indus river and ultimately drains into the Arabian Sea.

On first impression the road condition of the Karakoram highway was excellent except for occasional rock fall.

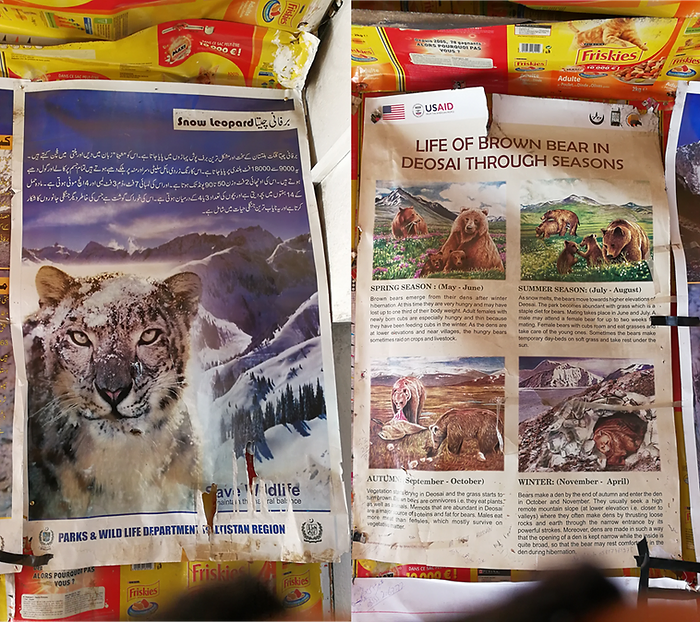

A sign from Gilgit-Baltistan’s Forest, Wildlife & Environment Department caught my attention. According to their website their mission is:

“Protecting, conserving, managing and developing the forestry, wildlife and allied resources of Gilgit-Baltistan through sustainable integrated natural resource management with a vision to develop the region as a biodiversity pool and a hub for eco-tourism.

Currently the Department is focusing on collaborative management of Protected Forests, Protected Areas and other biodiversity hotspots, Community-based management of Private Forests, creation of more protected areas with a vision to declare 70% of GB as protected areas, development of farm forestry through sustainable production of nursery stocks, consultative planning mechanisms including sectoral and thematic roundtables/interests groups through management plans and valley conservation plans, alternative energy sources and Payment for Ecosystem Services, alternative sustainable livelihoods, Institutional strengthening and skill development [and more]“

Taking responsibility for future generations, being clear on the values driving action, acting with a systematic long-term approach – respect.

We stopped at Batura glacier, one of the largest glaciers outside the polar regions. It’s flanked by an enormous western wall leading from the distant Batura Sar peak (7,795 meter) to the Karakoram highway – in the upper part the ridge stays between 6,000-7,500 meter for about 20(!) kilometers.

Here we met a group of Pakistani tourists who danced on the street out of joy to meet us.

Where does joy of life come from? Do you think it’s more something we “find” or something we “create” in our consciousness?

Joy seems to be determined by two factors – the “what” we encounter on our path, and the “how” we handle it.

Our feelings emerge naturally and don’t want to be pulled … so perhaps feeling joy is a consequence of several underlying things inside us and when we create the foundation for joy it automatically grows. Like practicing basic thankfulness (e.g. to be alive), having the courage to be our authentic self, and feeling which values we truly want to live by and then acting accordingly – everyone can practice these and many more “joy supporting things” daily.

And given that we are all connected … perhaps when we cultivate joy inside us it increases the joy inside others too. Why not open up to others with curiosity?

Usually we can learn something from other humans who are structurally on the same consciousness journey through life like you and me.

I’m just a cyclist and I’m just one of many cyclists in the world – and being part of the global cycling community feels good. And it’s not just the long-distance cyclists … everybody cycling just some kilometers in their hometown is part of this community, including people who just cycle occasionally on a rental bike.

Existentially seen, all cyclists as individual instances of the life form human enjoy the technology bicycle together – thereby bending the world towards a bicycle culture.

But do we only bend the “outer world” with our reality-bending force? I’m pretty sure that together we also bend the “inner world” of our reality and perhaps even the inner world of others … like when shared joy multiplies.

With whom do you like to share joy, dear reader?

In the evening we pitched camp above Passu – a small village with stunningly beautiful mountain views.

What brings us joy changes over time.

Our whole life package of joy and pain and everything in between, the whole existential stream of reality flowing through us from birth to death – I think this stream is something we all regard differently over the course of our lifetime.

Perhaps it’s more because we as the “observer” change and less because the “life we observe” changes? The existential stream flowing through us lifelong … structurally seen it’s kind of always the same thing.

Do our yardsticks change regarding our happiness and joy?

Empirical studies show consistently that beyond a pretty low salary level (allowing for an “ok life” …) more financial income does not increase people’s joy of life.

And measured on a macro scale, the populations in “wealthy” industrialized countries have clearly been found over the last 50 years to be “more and more rich” while people’s happiness has remained constant.

But within the lifespan of individual people, studies show that when people get older, they need less “extraordinary stuff” in life to be happy and rather find more joy and happiness in routine daily events – let that sink in for a moment … that’s pretty deep, right?

All other factors being equal (e.g. income, age, health …): do you think there is a key influential parameter for people’s happiness across their unique life paths?

The director of a long-term happiness study put it this way:

“This clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.”

What does all that mean for our joy of life?

We could give extreme answers like “I don’t care for empirical studies, my life is different!” or “understanding empirical patterns across thousands of people could be helpful for me – why repeat the predictable mistakes of others?“.

Personally, I sometimes feel an information overload – there are just so many studies out there. The examples above where all studies we discussed in my ethics course at the University of Kassel … I selected studies for my students aiming for constructive self-reflection impulses.

And then I think it’s good to also ask which other factors could play a role. For example, the cited study above found relationships (generally being social and connected, having friends) a key parameter to explain people’s joy of life – but had they asked for people’s degree of consciousness self-reflection perhaps that could have been another (possibly correlated) happiness driving parameter, or self-love, or meditative stability (in daily life), or having found meaning, … or a million other things. Perhaps they asked for some of those aspects … it’s probably tricky to precisely define and consistently measure them and I have big respect for this outstanding social science research project. But is reality only what we can measure?

Given our individuality we can probably generalize only one thing: what we perceive as things bringing us “joy of life” is highly individual and can change radically over time – tomorrow you will be different from today.

On a larger scale, what we perceive as a “meaningful human existence” may evolve along … or do you still care for the same things in your life you cared for 10 years ago?

Breathing in, breathing out.

When you already are at a beautiful place there is no need to rush or go somewhere else – and in order to go even slower, a biking fellow and I decided to let the others cycle ahead and spend a day exploring Passu glacier.

Pakistan has over 7,000 glaciers … more than anywhere on earth outside the polar regions.

Pakistan has an outstanding potential for eco-tourism – probably in every village along the upper Karakoram highway you can find a local guide and go hiking for days, explore truly wild places, or simply camp in the garden of a Pakistani family and enjoy life.

Do you sometimes also feel that everything around you is in balance, is in peace – and nothing needs to be added or subtracted to experience joy?

We left the glacier with a glowing feeling – Pakistan is a place where both people and nature make you feel alive.

On the highway we encountered almost zero traffic and the few vehicles and people we met made our day better.

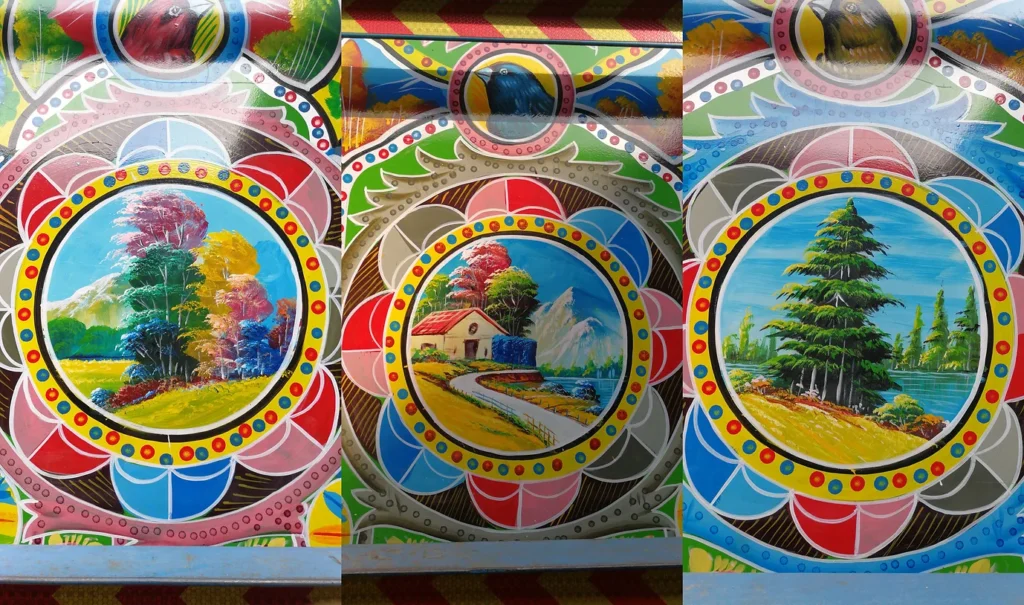

The Pakistani trucks are a pure expression of joy – each one is hand-painted and unique.

Finding food supplies on the Karakoram highway is easy – the small shops have everything you need.

In the afternoon we passed a lake created in 2010 by a massive landslide – at its peak volume the lake reached 20 kilometers in length, destroyed a long Karakoram highway stretch, and displaced 6,000 residents in upstream villages.

In the first year after the landslide, people were moved my military helicopter, then by boat until in 2015 five new tunnels and 24 new highway kilometer were opened – constructed jointly by Pakistan and China.

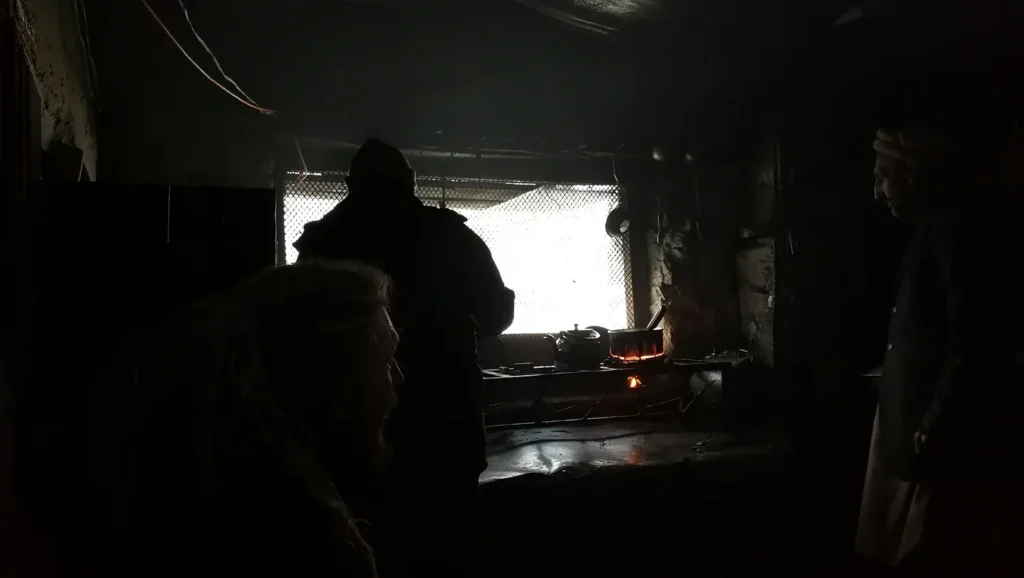

In the evening while we were looking for a camp spot a group of Pakistani soldiers invited us to stay at their outpost and cook dinner with them – we happily accepted.

When was the last time you connected to someone you didn’t know before?

Wherever we are we can form new connections with humans in the real world … creating joy out of exchanging stories, sharing knowledge, making friends.

Our hosts belonged to the Pakistan Army Corps of Engineers. At this outpost they were currently three: a driver (mainly to get water with a tractor and tank trailer), a medical soldier, and a commander.

In the last tunnel before their outpost there was still minor construction work going on, otherwise the new highway in this stretch seemed completed and our hosts were mainly protecting some construction material and two mobile heavyweight cranes.

Over breakfast our hosts shared more stories from their life.

I felt respect for them – the army engineers work in the Himalayas all year and the weather conditions in winter can be rough.

Pakistan is the world’s fifth largest country by population with 240 million inhabitants of which 1.5 million live in Gilgit-Baltistan. The Karakorum highway is Pakistan’s only land border crossing with China.

Building roads, building tunnels – whatever we construct as humans we remain biological beings, right?

Who knows how joy works. Perhaps there is something woven through humanity, woven through us all as individual parts of the large web of biological beings, woven through biological life itself.

Do you sometimes feel the biological life inside yourself driving you perpetually forward?

It’s the same force that creates beauty …

Near Karimabad we stopped to explore a site with ancient rock engravings – this is just the tip of an iceberg as thousands of different rock engravings have been found in Hunza valley made in various different writing systems over centuries.

Some of the engravings in this area are Buddhist. Who knows, perhaps Buddhism and Zen ideas were brought from India to China along this route and monks carved some of these rocks to leave messages for future generations?

In the afternoon we reached Karimabad, previously called “Baltit”. The city was renamed honoring Karim Aga Khan who is the spiritual leader of Isma’ilism (a branch of Shia Islam) and founder of the Aga Khan Development Network – a global development network focused on helping people in need irrespective of their origin, faith, or gender.

We got food supplies and then cycled (and pushed our bikes) up a steep path above town to find a campsite with a view. This valley was simply too beautiful not to be viewed from a campsite 2 hours up from the highway.

We pitched camp with a glowing feeling – Pakistan is a place where both people and nature give you energy.

What do you think about the relationship between consciousness clarity and joy?

Perhaps the more important question is how you feel about it. In today’s world we are used to give “language” and “knowledge” and “mental maps” much consciousness attention .. as if these cognitive things were the only source of wisdom.

But when we look at our biological brain from an evolutionary perspective, our feelings were there first and still today our feelings sit deeper inside us than all the cognitive talking we added later in our development as a species.

How do you find out if you really love somebody? Is it by observing the “words” you think about that person, by writing down your thoughts in “words”, or by talking about your relationship in “words”?

No. You only find out if you really love somebody by directing your consciousness attention to the feelings you perceive in your belly and solar plexus region. And when these parts of your body feel kind of warm and glowing – that’s where you find the true answer without any “words” added to your feelings.

Consciousness clarity about our feelings, body, and thoughts in combination is a full perception of who we are … and being a balanced and authentic self-reflected person probably helps us to cultivate joy – when we see the whole picture of who we are, we see clearer all the things we can appreciate.

We got up in the dark and hiked up higher to watch the sunrise over the valley.

Was the sun rising “out there” or “inside our consciousness”? Who knew, perhaps both.

We decided to stay another night at this campsite. Why go somewhere else when a place is great?

In the afternoon we cycled down to Karimabad to spent time with the other cyclists with whom we had crossed the border. As the China experience was fading away, everyone was smiling and feeling relaxed again.

Karimabad is surrounded by glaciers, high mountains, pristine forests, and a river. The locals are warm and welcoming – this city is a fantastic place for eco-tourism offering everything an adventurous traveler can dream of.

In the evening we bought food supplies, cycled up again for 2 hours to our campsite, and watched the sunset talking about life.

All cyclists left Karimabad today, but I decided to stay.

I wanted to really be in this place, to connect to it, to feel it. And I wanted to learn more about the local life – hadn’t I started this whole bike trip to learn more about how other people live and view the world?

The Pakistani man who let us camp on his ground operated a small restaurant where he also let me use his kitchen. He told many stories about the local life, the challenges, the hardship, the high infant mortality rates, the developments in recent years – and about his future plans to host more travelers on his site.

What impressed me the most was the clarity of his values based on which he lived his life. He was selling self-grown apples on the roadside and the way he handled them showed that he visibly cared for each individual apple. He explained to me in detail his life perspective to grow his business slowly, sustainably, and out of his own strength. Despite all challenges and hardship he faced, he was living his life based on respect and love for all beings and he cared for the well-being of others just like for himself. His outlook on life impressed me.

What do you think about the relationship between joy and oneness?

In Isma’ilism, the main religion in Pakistan’s Hunza valley, oneness is a foundational concept. The Ismaili interpretation of reality is that god exists in everything.

With this pantheistic interpretation, god exists and unfolds through every aspect of our body and consciousness all the time … including our feelings.

Hunza valley has been praised internationally as a place of tolerance, pluralism, equal rights, literacy and progressiveness – was the joy of life you could see and feel here perhaps a result of the people’s belief system?

A reality interpretation with an element of oneness is of course something very common in the history of humanity across cultures and continents and time. And you, dear reader, perhaps you also think or feel into oneness ideas sometimes.

Why did you decide to explore your consciousness in the first place? And where has your individual path of self-exploration led you so far?

I think we all are consciousness explorers … it seems to be part of our natural human condition to self-reflect and feel beyond the edge of our consciousness with curiosity. What’s out there for us to discover?

I believe that there are as many valid reality interpretations as there are humans and I think your concept of making sense of the world is equally valuable and important to mine – aren’t we all just different lenses breaking the same reality?

The curiosity we have to explore our own consciousness … probably it can only be paraphrased in words – particularly regarding reality aspects which are deep.

But the curiosity inside ourself is undeniably there, driving us all perpetually forward as consciousness explorers. And even though we can’t articulate a final reality interpretation in words, we can all find elements of answers in our feelings.

I think that we all know one way or another that there is more to life than (only) the superficial input stream created by our bodily senses like seeing, hearing, smelling, and so on. Somewhere deeper than that, perhaps foundational for our entire reality, there seems to be something else … something we can feel.

Is reality perhaps easy and natural?

If there is something like an eternal higher spirit, it already existed before the evolvement of humanity’s language-based reality concepts and the analytical complexity created by our modern world. Some people like Indigenous tribes may never “study” texts on oneness but they should have the same possibility to connect to spirituality like people reading tons of books on the subject … maybe they feel spiritual things even better without a word-contaminated consciousness?

If the universe consists only of non-spiritual base elements, pure dead atoms driven by the law of physics only … then we can equally feel into oneness, into the physical space around us containing everything.

Perhaps concepts like pantheism and atheism become equally dissolved when we calibrate our consciousness attention on our direct feeling experience. Perhaps the flavor of the energy we perceive in our belly and solar plexus region is where we find some answers we are all looking for … who we truly are, how reality works, how to have some fun in life, things like that.

Time to cycle from Baltit to Gilgit – Pakistan kept touching my heart with its beauty.

In Ali Abad someone wrote on the mountain flank above town in giant white letters: “PEACE – RESPECT – TOLERANCE”.

The literacy rate in Hunza valley is 97% among both genders and most of the young people here have professional degrees – basically everyone speaks good English.

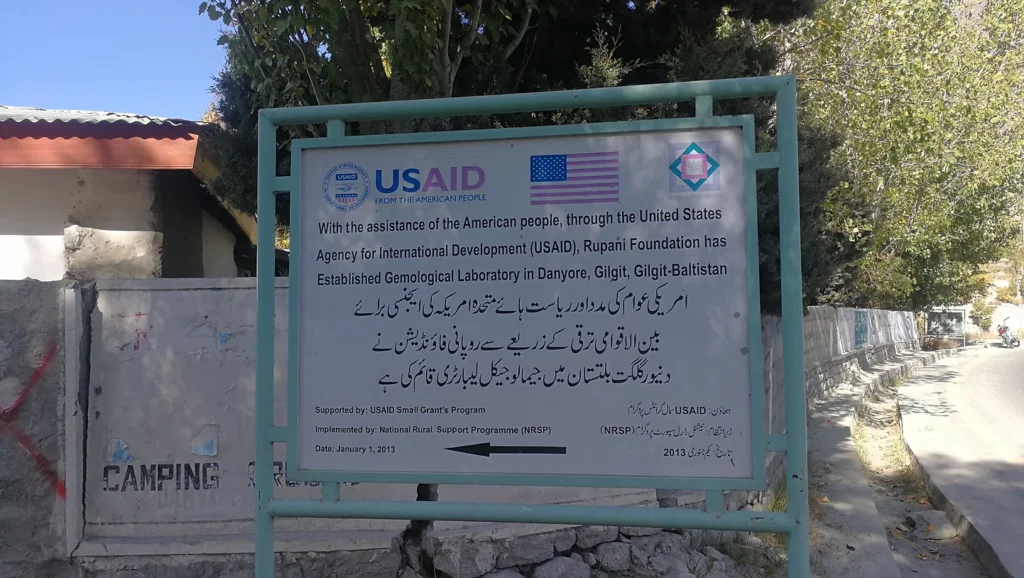

In several villages in Pakistan I saw signs from a Pakistan-US collaboration program which has been ongoing for over 70 years.

It this part of the Himalayas I expected winter conditions just to realize that Hunza valley is famous for the cultivation of fruits and it was still harvest season – people here grow mainly apples and apricots, as well as cherries, grapes, peaches and melons.

The plurality and colorfulness of this region is also reflected in the many local languages – in Hunza valley alone, common languages include Burushaski, Shina, and Wakhi. I assume they are spoken in parallel to Urdu and English which most people seems to speak.

Northern Pakistan touches you in many ways and gives you new perspectives – Rakaposhi peak (7,788 meter) is just about 10 kilometers horizontally away from the Karakoram highway but is vertically 6 kilometers higher.

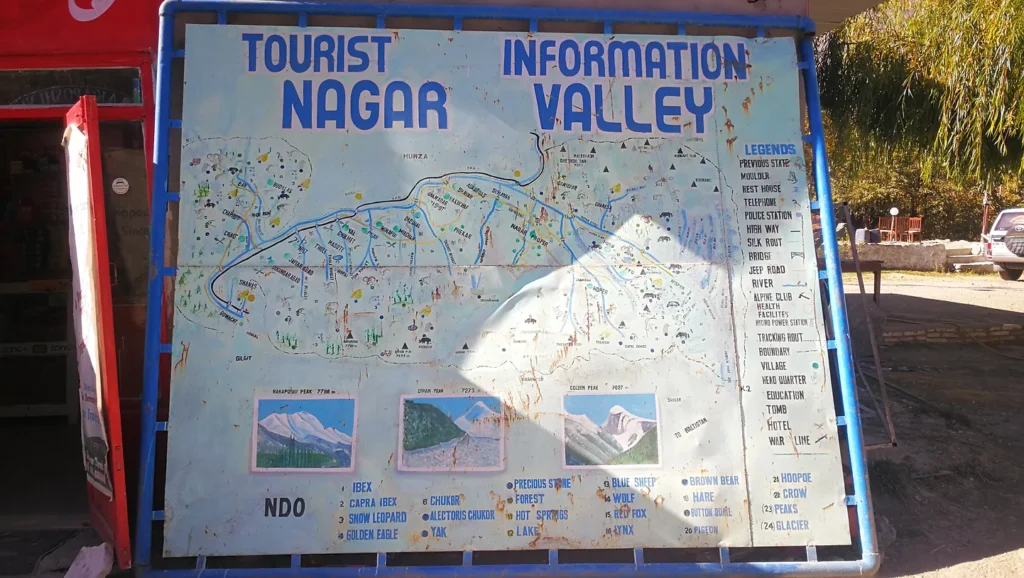

Nagar district south of Gilgit-Baltistan’s Hunza district is equally charming – the people here are warm, welcoming and educated, and the nature is simply amazing.

In Ghulmet I stopped for a tea and chatted with locals. This village is roughly at the northwestern end of the Karakoram National Park – a large biodiversity protection area created in 1993. The park contains sixty(!) 7,000 meter peaks, four 8,000 meter peaks, many glaciers (38 % of the park area), and a variety of ecosystems.

What stands out when you talk with the locals here are their clear convictions regarding the value of nature. Living in balance with nature and protecting it has always been their way of life … long before terms like eco-tourism got invented.

What does joy mean from a biological perspective?

Being a part of nature, we are all connected as embedded life forms, we are all connected in the overall system of biological life. Thus when a human feels joy, a part of nature feels joy.

Perhaps feeling into nature can be deep and healthy way to explore our consciousness. Perhaps feeling into nature can also be a step towards feeling oneness.

Hows does it feel when you sense into the biological life system surrounding you? And how does it feel to be biologically alive?

When you cut your finger you bleed and your blood is warm, right?

The human web connecting us all, our embeddedness as biological life – are these perhaps core sources for our joy?

Perhaps joy is less something for us to consume individually, that also, but rather something reciprocal … something biologically connecting us.

Whether your world concept contains atheistic or spiritual ideas – have you ever reflected your biological life as a part of our ecosystem?

Perhaps when we fully accept our biological death, we feel the most joy of life … limited things, like our lifetime, are valuable.

Who knows, perhaps thinking about our limited human lifespan is a good start to find joy but looking at the world with much longer time scales is where deeper joy can be found – have you ever tried to feel into infinity?

Try it for a moment …

Breathing in, breathing out.

I pitched camp in the garden of a hotel in Rahim Abad and chatted for 2 hours with the owner – a man who impressed me both with his strategic foresight and clarity of values.

It was not just that education for his daughter was one of his priorities. He had a detailed understanding of different long-term career implications from studying civil vs. mechanical engineering which he reflected in an international economic outlook.

In the morning I cycled past a jewellery making training center in Danyore – developing a sustainable value chain sounds smart.

Perhaps “being fair” to people making things can bring us joy? Many very real people across the globe produce many things we consume daily.

In the early afternoon I left the highway and cycled into Gilgit to meet my fellow Karakoram cyclist again – Gilgit is situated in a broad valley where the Hunza and Gilgit rivers merge.

At the entrance gate of Gilgit I drank tea for one hour with the friendly military police and listened to their stories. The commander just came back from serving a year for the UN blue helmets in Congo – the engineering corps commander who hosted me some days ago had served a year for the UN blue helmets in the Central African Republic.

Pakistan is currently the fifth largest global contributor of uniformed personnel to UN peacekeeping missions.

Gilgit is a lively town and a hub for trekking tours and mountaineering expeditions in the region – I liked the energy of the place from the beginning.

I didn’t know what to expect when a fellow cyclist texted me “come also, there is space”.

It turned out a Pakistani man had offered his massive house and garden to our group of cyclists without even being there himself. He had simply said “make yourself comfortable and stay as long as you want” … the hospitality and generosity of Pakistanis are amazing.

Joy of life – how is it related to hospitality, generosity, and the general act of giving?

Perhaps people with more joy of life give more, perhaps people who give more have more joy of life, or perhaps it works both ways.

In my view, giving is not limited to having “money” or “property” or “possessions” – even when you own nothing you can always give a smile or encouragement or a million other things which change people’s life for the better.

And I believe that giving changes our own life too. Just imagine all the processes happening in our consciousness through our acts of giving … things like growing the good side of our human nature, increasing trust in each other, letting go of our self-focus, and co‑creating a reality we authentically like and we are proud of.

The house in Gilgit was an oasis of tranquility and peace and so large that we could all sleep inside. Not just the owner wasn’t there … except us cyclists there was nobody at all.

Would you offer you house and garden to a group of foreign cyclists without you or someone you know being there?

Whenever I receive such trust, I feel inspired to give back the same to the world myself.

The rooftop allowed great views over Gilgit river and the valley – the entire Himalaya and Karakoram region was so different than I had imagined before coming here.

The house where we stayed probably belonged to a farming business, at least they had a sign on a solar-dryer for apricot dehydration at the entrance.

In northern Pakistan, over 50 different apricot types are grown but selling them at distant markets requires a smart value chain of this perishable product. The traditional rooftop drying technique is labor intensive and leads to dust on the fruits – closed solar-dryers work faster and the farmers also get higher prices due to the better product quality.

In the afternoon I went to Gilgit downtown with a fellow British cyclist to get food for a large group dinner in the evening.

A fantastic thing I had missed were bananas. I didn’t see a single banana in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and in China the bananas tasted metallic. But here in Gilgit they sold delicious sweet bananas from Pakistan’s nearby subtropical parts – 100 Pakistani Rupees (0.4 Euro) get you 12.

Gilgit is a lively town where people are joyful – people here definitely use their reality-bending force for the good.

It was time to say goodbye and leave the oasis.

Perhaps finding joy in life is about balance. Always staying in a protected oasis would be pretty boring – like not being born. And always being out there on the road would mean never having time to pause and integrate the experiences we make.

Perhaps our entire life path is a practice in coming to our middle. Perhaps when we learn to discover who we really are, we naturally develop this deep and joyful smile we immediately recognize in people who have found a balance in their heart.

It may, however, take all our lifetime to get there. And probably it requires us to get “out there” … be it in Gilgit-Baltistan or wherever you live right now, dear reader.

Who knows, perhaps the life path of every human has a deeper meaning which everyone can only find individually by practicing consciousness awareness?

Cycling of out Gilgit I had a melancholic feeling. Islamabad would be just 4-5 cycling days south but I felt like spending more time in the Himalayas.

At the intersection of the Gilgit river and the Indus it was time to give everyone a hug and say goodbye – two cycling fellows and I decided to leave the Karakoram highway to cycle a 9-day side loop to Skardu and Deosai National Park, and the others headed south.

We crossed the river and began following the Indus upstream.

The Gilgit and Indus river junction is a common definition of the meeting point of the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayas – the three highest mountain ranges in the world.

The rock color changed as soon as we turned into the Indus valley where layers of black and white stones appeared.

In the evening we found an empty house under construction where we slept for the night.

Joy of life – what if there is a big web of joy woven through us all?

The oneness thing, it has different aspects to it as I’m sure everyone already knows and feels one way or another.

Transcendence into something like a “cosmos-wide-feeling consciousness” – that may be possible if we practice for a really really long time, or not … I don’t know.

But wherever we are in our life, we can always connect a bit more with the humans next to us, spend time together, form friendships.

I think “feelings towards oneness” can be experienced by everyone in our daily life – practicing humaneness doesn’t require existential philosophy at all.

And sharing joy of life – it somehow makes our life experience lighter and deeper at the same time …

Coming from the Karakoram highway, the road to Skardu follows the left bank of the Indus in increasingly steep terrain.

The Indus is a river with many stories to tell. It springs in Tibet, then flows northwest through India’s Ladakh region past places like Leh, then flows further northwest into Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region where it finds its way between four 8000 meter peaks in the north (K2, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum I & II) and an 8000 peak in the south (Nanga Parbat), then it turns southwest and merges with the Gilgit river, until flowing down all the way to Karachi where it drains into the Arabian Sea.

The Indus is definitely cool.

In Sassi we found fresh daal (lentils) for a second breakfast.

We passed Haramosh peak – famous both for taking mountaineer lives and for his beauty.

South of Sassi we met a US film crew making a documentary about kayaking on the Indus.

The local guide of the kayak crew told me that he had worked for hunters before – the license to shoot this mountain goat cost 95,000 USD.

The introduction of trophy hunting schemes in Pakistan has been a big success in biodiversity preservation. 80% of the hunting license fees go to local communities who now protect local wildlife instead of hunting it in large numbers themselves. And given that only a couple of old male animals are shot per year, the overall wildlife population is increasing steadily.

Our daily sleeping elevation gain from the Karakoram highway up to Skardu was moderate but I would estimate we still cycled 2000 meter uphill every day given the constant up and down along the Indus.

In Shangus we drank a tea and chatted with truck drivers.

The truck paintings are made by hand. While being pieces of art, the Pakistani trucks are workhorses delivering all kind of goods to the mountain villages.

Just like the Karakoram highway it must have been challenging engineering work to build the small roads in this region, like the one we followed to Skardu.

Have you ever noticed that in the mountains for about 5 minutes after sunset the last light has a blue touch?

The day transforms forward into the night, which in the morning transforms forward into the next day, and so on in a perpetual cycle of change.

Of course, not just the days and nights transform forward, it’s the whole reality including ourself – our bodies, our feelings, our consciousness or perhaps “soul” … depending on your world concept and how you prefer to call things.

And while we all face constant hardship in the stream of change we experience from birth to death, the reality-bending force we possess can make this ride joyful. Not just for us individually, that also as we are ultimately free inside to feel what we want, but for the larger web of humanity.

I don’t believe that traveling externally is a prerequisite to connect deeper to our reality – where you are in this moment as you read this is just the right time and place.

But then again traveling and existential philosophy have always mixed well, perhaps because new stimuli make us more awake, or perhaps because traveling gives us inner freedom.

Of the many travelers before me I would like to thank a particular one: Robert Pirsig, an American writer and philosopher. He wrote “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values” – a masterpiece which among many things contrasts rational-analytical with romantic-emotional ways of life, reminding us with clarity:

“What is seen now so much more clearly is that although the names keep changing and the bodies keep changing, the larger pattern that holds us all together goes on and on. In terms of this larger pattern the lines at the end of this book still stand. We have won it. Things are better now. You can sort of tell these things.”

“The larger pattern that holds us all together” – it’s a deep answer and perhaps the central one for consciousness explorers across cultures and times.

Yesterday evening we had reached a small mountain village in the dark where we simply slept on the floor. In the morning we took our time for breakfast, thanked the locals for their hospitality, and starting cycling.

One reason I love mountain roads is that they are full of surprises and you never know what’s around the corner – just like life.

This road brought back memories of the Pamir highway where you can equally look into people’s lives on the other side of the river – cycling here felt like watching two movies at the same time.

In Astak we stopped to drink a tea in a beautiful garden by the river.

I like the way people in Pakistan drive – compared to other countries drivers here give you more space as a cyclist and generally drive conservatively.

Some transportation forms here are pretty innovative … I would totally try this too.

Near Harpo we passed a sign on a sustainable hunting project overseen by Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change – definitely cool.

The Indus has something special. I can’t describe it in words but feeling into this river is different from other rivers.

“The larger pattern that holds us all together” – how does it express itself? Existentially seen, one could say through everything, including rivers and mountains and all that.

But human encounters somehow have a special place in it … you can sort of feel it when you shake somebody’s hand

You can feel it too when you pay attention to the giggling of children playing in the street.

But it’s not just on the surface where you can feel it, also deeper through the way things exist in general. Like when you experience that the locals generally accept you as a traveler passing through their community, that’s there independent of individual people.

It almost seems like on a deeper level, the world is glued together by our feelings for each other. And brotherhood and sisterhood, this natural solidarity and wishing-others-well among humans … it somehow seems to be a core element of the world’s fabric.

The larger web of humanity is real – it’s not just a philosophical idea, just like our reality-bending force. You can feel both clearly when you look into people’s eyes and learn their names – they too are breathing, they too have a beating heart … just like you.

In my experience, people are usually curious and supportive across countries … of course more when you are an “interesting” cycle tourer, but I think a basic human solidarity is always there among all people under all layers of stereotypes and fears.

Would a sane person really wish someone else something bad?

Do you wish someone else something bad?

How do we put human solidarity into action? The development projects in this area all seem to focus on strengthening local communities – “strengthening” others, not “weakening” them … I think a sane person generally does that.

I felt respect for the people living here – it takes courage and determination to live in remote mountain areas where harsh weather and challenging life conditions are standard.

In exact contrast to the harsh life conditions, the people in Gilgit-Baltistan are warm-hearted and full of life energy – perhaps overcoming challenges brings out the best in us?

When was the last time in your life you stopped and soaked it all in, the whole reality, and you felt that everything around and inside you is in balance, is in peace – and nothing needs to be added or subtracted to experience joy? Have you ever felt this balance at all?

With your reality-bending force, you can choose the direction and underlying emotional flavor of your consciousness attention whether you are in the Himalayas or where you live right now. And with those two parameters in your command, an inner balance is something you can let grow for sure.

I think we all feel a certain longing inside to find this balance, to perhaps re-find it.

Where the road reached the Skardu plateau I was impressed by two things.

First, by the enormous dimensions of what I would call an “Indus plateau delta” – about 10 kilometers long and 3 kilometers wide.

Second, by the fact that nature here has remained untouched. No hydroelectric power generation, no taming of the river, no human settlement as far as the eye can see – I find it truly amazing that such places still exist on earth.

The Central Karakoram National Park is on the tentative UNESCO world heritage list – fingers crossed for a full status!

This area is not just unique in terms of nature and wildlife … the glaciers of the larger Himalaya region are also the freshwater source for over 1 billion people.

The Skardu road was built 1979-1981, and the Central Karakoram National Park was founded 1993.

South of the Central Karakoram National Park lies Deosai National Park – one of the reasons we came here.

In the afternoon we reached Skardu – the gateway town for K2 expeditions.

K2, the world’s second tallest peak, is technically extremely challenging to climb … this is a mountain you don’t climb with physical strength only.

Do we create joy by overcoming challenges?

I think challenges are good for us. I think challenges are healthy.

But I disagree with people framing the “overcoming” part as a central requirement to feel joy. It’s really ok to just exist. In my view, our reality-bending force can be directed to deeper things than “achievements” in the external world. There is nothing wrong with climbing difficult peaks as long as it’s done with respect for nature, local communities, and ourself. But I think the really rewarding peaks are found in our internal world.

Have you ever worked on forgiving someone? It’s hard.

And who is it “achieving” something? Yes it can be ourself … but it can also be a human sister or brother whom we support, and that can be an equal source of joy like our own achievements.

Is the large web of humanity perhaps “achieving” something jointly all the time? Carrying humanity’s biological life forward, maintaining a solidarity baseline in the world’s fabric, co-bending our shared reality … I would say yes.

“The larger pattern that holds us all together” – how much joy of life can we find there?

In the morning we left our hotel early and got food supplies for a couple of days, then we cycled out of Skardu southbound.

Skardu has a lively center but a calm feel in the outskirts.

Pretty rough road near Satpara lake – my cycling fellow broke several spokes on his back wheel but replaced them skillfully fast.

At the national park entry checkpoint we did a quick registration.

We pitched camp in the early afternoon near the road. No other humans were around in the valley – we didn’t see anybody during three days in the national park.

My cycling fellows had a clever tool for cooking with firewood. The yellow base creates a chimney effect, holds the fire together, provides wind protection, and allows feeding the fire from the bottom. You can directly cook on it, or first place the intermediate hollow water jug on it so you automatically get boiling water while you cook on top. Definitely cool.

Clear night, a million stars, feeling free.

Do you think feeling joy requires freedom?

We are all existentially free inside to give our consciousness attention to anything we like and we can give any type of attention that feels good. But being existentially free does not necessarily mean that we are aware of this freedom.

Thus to truly feel the joy of inner freedom, perhaps what we need to practice is a conscious awareness of our freedom – an awareness of the unlimited choices we make inside at any moment of our life while we constantly transform forward.

Inside our consciousness, the opinions of others ultimately don’t matter, or at least they only matter to the degree that we choose – inside our consciousness we are definitely free.

Breathing in, breathing out.

Steep uphill cycling in the morning – the advantage of steep roads is that you cover vertical gain quickly.

At 13pm we reached the Deosai plains – respect for the Himalayan brown bears living on this plateau.

Pretty rough road – on some sections I went with snail pace to avoid wheel damage.

Deosai means “land of the giants” in the local Balti dialect which is an old form of Tibetan. Perhaps a reference to the giant mountains surrounding the plateau?

The Himalayan brown bears have the spotlight here but the national park is also home to a population of Tibetan wolf.

Nobody was around in Bara Pani – in summer it’s a popular camp spot for park visitors.

We would have been happy to camp … but found two alien spaceships to sleep in – perhaps designated shelters anyways?

Consciousness – do you understand yours?

My perception of the field of consciousness research across all disciplines is that nobody really knows how the human consciousness works. People articulate theories and metaphors and opinions, but basically they all differ.

Perhaps our consciousness collapses the quantum wave function (so we see a “stable reality”), or perhaps the wave function collapse leads to our consciousness (so “we” exist as stable observers) … I’m just a cyclist, I have no idea.

Is “knowing” relevant to feel joy of life?

The Zen people advice against the usage of words just like spiritual thinkers across cultures and time have stressed the importance of detachment from language-based concepts. But words can probably be helpful on our life journey as intermediary steps when we sort out our reality in a way that works for us.

When we feel joyful, when our mind is calm, when we look at the world with a relaxed smile and our heart is full of compassion for ourself and others – this state of existence is probably a result of having previously sorted out things in our consciousness.

Like our thoughts and feeling, like our past experiences and future plans, like our assumptions how reality works … things like that.

Following the feeling of joy of life, following generally what feels good and true in our consciousness – this life compass works independent of word-based “knowledge” so who knows … perhaps we can already feel good and joyful while we sort our reality out?

Calm night but I underestimated the cold – in the morning it had -10°C/14°F inside our closed spaceship and my water filter was frozen as I hadn’t taken it inside my sleeping bag.

Breakfast, sunshine, let’s go cycling.

Right or left? It probably doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things – there are going to be stones either way.

Fire and ice … I kind of like the combination.

I wonder what the brown bears living in the Deosai plains eat. It’s impressive that they find enough calories at 4,000 meter elevation to get sufficiently fat for a comfortable hibernation.

I felt strange realizing that we had already crossed Deosai National Park. I would have liked to stay longer but that’s life perpetually transforming forward.

The downhill towards Chilam was a dream – smooth tarmac, gradual elevation decline, and stretched-out until the horizon.

The unknown behind the horizon is just something we don’t know yet – the unknown is our friend.

We are all perpetually transforming forward. Today you are a different human from yesterday, and tomorrow you may die. Of course our whole reality perpetually transforms forward.

So facing the “unknown” is a constant in our life … how does that feel?

What we encounter behind the horizon will be a mix of pain and joy – that’s for sure.

Perhaps pain and joy can equally become a source of energy?

Existentially seen, we will keep existing as a consciousness just fine as long as our biological life continues – we can take a deep breath in and rely on that.

In my view, the unknown is always a chance, both in the external world and inside our consciousness. To me horizons of all shapes and colors are attractive … what may we find beyond?

I think having fears of the unknown is a natural and healthy reflex (which evolutionary served to protect us) – but I also think that we can balance it with excitement about the unknown.

Why not? It’s free and energy releasing at the same time …

Given that we are free to choose the direction and underlying emotional flavor of our consciousness attention, we can all make the unknown our friend by bending our reality that way. And it doesn’t require any existential philosophy … cultivating a general attitude of joy to be alive is all it takes.

Sometimes I wonder if we all already know and feel that there is more to life than our superficial reality (forms, shapes, colors) and that we just don’t talk about it a lot. Why not?

We all have the force inside ourself to co-create reality. To me that’s the most normal thing of the world, as is your ongoing inner dialogue about who you are and how the world functions.

In Chilam we wanted to camp but the locals invited us to sleep on the floor of a tea restaurant.

Around 21pm when we were just getting ready to sleep there was yelling outside – three brown bears had torn down a stone wall of a storage house to feed on grain supplies.

In the morning I got up early and went for a walk. Chilam is small and has a friendly and relaxed atmosphere. From here the road south leads to India and if you could cross the border you would soon be in Srinagar or Leh.

The local were not angry that the bears had come yesterday night for the grain supplies … apparently a large part of what the bears eat is grass.

Sure the bears bring tourists to this community but I think the locals were relaxed about the bear incident for other reasons.

In my perception, the people living here see nature as something valuable, something they are part of. Not complicated based on long philosophical considerations … but rather simply because this is how things are.

We thanked our hosts for their warm hospitality and left Deosai National Park northwestbound following the Astore river valley.

The few settlements in this valley seemed centered around cattle and sheep farming and some low-key agriculture. Pakistan is so rich in values it’s an inspiration – I’m from a nation of automakers but driving cars stopped being cool last century.

Gentle downhill rolling, sun rays in my face, varied landscape and vegetation – cycling this stretch felt amazing.

Do you think we can feel freedom and joy wherever we are?

Perhaps we can when we make it a habit to appreciate the little things in our daily life. Like noticing the temperature and smell of the air we breathe, or the gentle perpetual change of the clouds happening perfectly fine without any effort required by us.

Nanga Parbat – the 8,126 meter peak has many stories to tell. On its north side the mountain rises from the Indus and Karakoram highway 7,000 meter up, and the south side is one of the biggest mountains walls on earth.

It’s a mountain that has taken many mountaineer lives. For example in 1970 the two Messner brothers made an ascent via the Rupal Face and one of them disappeared during the descent – his first boot was found in 2005, the second in 2022, which allowed the reconstruction of his descending route.

The road we took looped from the Deosai plains past Nanga Parbat back to the Karakoram highway. Next time I would cycle to the village Rupal at the foot of Nanga Parbat (23 kilometer west) or visit the northern basecamp (15 kilometer from the highway) … I don’t know how cycleable these roads are but what should go wrong when you bring enough food?

All locals we met in this region were warm and welcoming. In my view they were not just happy to see foreigners, but rather people here have compassion for the world and others in general … you see it in their eyes.

In Makiyal we stopped for a tea and rotis.

If you turn left here you reach the foot of Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face.

The Skardu loop tested the limits of our bikes as the roads on the Deosai plains were truly rough: my fellow cyclists had a combined 6 flats, 2 broken spokes, as well as a brake holder broken out of the bike frame and a backrack mount broken out of the bike frame – both needed welding.

Due to the required welding we decided to split up – the others will hitchhike to Islamabad and I kept cycling down the Karakoram highway.

On my bike a metal front bottle holder broke off (due to the vibrations) but I can easily live without and just put the bottle in a bike bag.

I also lost the gasoline bottle for my stove. The bottle must have come off due to the bumpy road – I should have mounted it better. Until I find a replacement bottle (with an integrated fuel pump), or gas cartridges fitting the stove, I will cook on fire.

The lost gasoline bottle with fuel pump costs about 100 Euro – more than I spend in the last 17 days in Pakistan in total. Finding a replacement bottle in Pakistan would perhaps be tricky but I assumed to be able to find a simple replacement stove somewhere, perhaps burning paraffin oil.

We camped next to a river and cooked dinner together – the last time after cycling together for nearly three weeks.

Joy seems to be something we can create alone – a little twist of our reality-bending force is all it takes.

But joy is also something we create and grow together and when shared, it definitely multiplies.

We packed up camp early and continued the downhill. We had slept already 2000 meter lower than the Deosai plateau and today we would drop down another 1000 meter in elevation.

Also today friendly smiles by locals greeting back while we cycled through their villages.

One of the many things the people in Pakistan impressed me with was their courage: their resilient attitude towards life, their full-hearted optimism, and their vitality. Their general life attitude seems to emerge from a deep trust that on their path they are going to be fine … it has something uplifting.

This attitude is a result of how people here use their reality-bending force. Every day they choose to handle life’s challenges upfront (attention direction) and they choose to do so with a positive and constructive attitude (underlying emotional flavor).

Pakistanis bend reality from the infinite number of possible trajectories towards a society based on love for life despite all hardship and challenges – this attitude has my respect.

We stopped at a bridge built next to ruins of an old bridge – even the small rivers in this region seem to become torrential streams in times of heavy rain and snowmelt.

Perhaps the joint coping with environmental hazards give communities here part of their strength?

And it’s not just floodings that can destroy roads and bridges – mountains live, and in some areas boulders the size of a car may roll down the slope at any time.

Perhaps the only way to find lasting joy in life is to come to our middle – to fully accept our life with all feelings it brings.

I think that in the long run life is fair and that the hurdles it gives us have a deeper meaning. Like strengthening our resilience, teaching us who we really are, things like that.

Who knows … perhaps at night when we sleep the universe shuffles our souls within humanity’s collective zeitgeist and every morning we wake up as another person living another life for a day.

How fair would that be existentially seen!

Like that we would all use our individual reality-bending force for a day, but the nightly soul shuffling would make it a zero-sum game if we win or lose in life relative to other people (however you prefer to define that).

And if all our life experiences are part of a collective reality-bending force … well, perhaps we would cultivate more team play. If I am you tomorrow, then treating you well today is kind of an investment in my future self.

We reached the highway from where I cycled alone. It was a good experience to cycle with others – you definitely laugh much more on the road together with friends.

In the afternoon I raced down the highway along the Indus, bursting with energy.

Pakistan is an amazing country for adventurers and explorers – and particularly suited for expeditions into your soul.

I cycled into the evening and got invited by the Gilgit-Baltistan police to camp in their station in Gunar.

How do we calibrate our reality-bending force usage?

There are as many right answers as there are humans given that our individual life paths are part of the answer.

Some people benefit from practicing body-awareness (e.g. paying attention to their breathing and body-sensations).

Some people benefit from practicing emotion-awareness (e.g. letting their feelings arise and allowing oneself to fully feel their feelings without any analyzing words).

Some people benefit from practicing narrator-awareness – clarity about the words in their consciousness, clarity about their individual mental maps used to make sense of the world.

I mean “benefit” in the sense of moving into a direction people like … a life direction that feels authentic and good to them.

So across our body, feelings, and thoughts: how do we calibrate our reality-bending force usage?

Perhaps feeling our entire mind-body-bundle simultaneously is the simple answer … how else can we navigate life with balance?

In Gunar I noticed the first time a higher humidity than further north on the Karakoram highway – even so Nanga Parbat was just 25 kilometer away.

I had thought about taking the N15 road leading to Mansehra via Babusar pass, an alternative to the Karakoram highway. But at the intersection I was told the pass (4,170 meter) is already closed due to snow and I’m generally unsure if you get permission to cycle there as a foreigner.

From Chilas to Islamabad cycling along the Karakoram highway is not recommended – I respected the custom.

At the traffic checkpoint his colleagues invited me for lunch, then they asked a pickup with enough space to take me along to Besham city.

I went with an empty pickup but on the way we picked up goods and another passenger.

We went to a hotel and when I asked for the possibility to camp the friendly staff was happy to let me camp in the hotel garden.

I decided to stay a second night in the hotel garden – a peaceful and meditative place directly at the Indus.

When you cycle over the Himalayas, it’s when you feel a subtropical flair that you begin to realize you will be out of the mountains soon. And in our consciousness, how do we realize that we have crossed a mountain there?

I think it’s similar. At first you don’t notice anything as there is no tangible “bang”, no clear demarcation line separating the “before” from the “after”. What you notice at some point is a subtle flair inside yourself, a feeling slowly emerging at the edge of your subconsciousness.

When you cycle down the Karakoram highway coming from China, you can’t clearly tell when things change not only due to the gradualness of change but also because what changes is multi-dimensional. The landscape, vegetation, temperature, humidity, sounds, smells, road condition – these are just some of many aspects gently changing between Khunjerab Pass and Islamabad.

In our consciousness this too is similar as our reality is multi-dimensional … what else would the constant flow of the general existence of things be? Thus when we cross a mountain in our consciousness many things gently change simultaneously while we bend our unfolding reality towards a direction that feels right – towards a direction that feels better.

Perhaps the largest and most profound changes in our consciousness happen automatically and structurally similar for everybody over the course of our lifetime. A change from a focus on ourself to a focus on others perhaps, a change from rejecting what we don’t want towards a universal acceptance of how things are, or an attention shift from words to feelings … who knows!

Breathing in, breathing out.

From Besham I cycled 50 kilometer south along the Indus accompanied by a police officer on a motorcycle, then at a checkpoint his colleagues offered me a ride. In Pakistan you can fully trust the police and my view it’s the right thing to take their advice.

I got transferred to the next police van a couple of times – the police crews here work seamlessly together to ensure a fast and easy transfer for you and your bike.

The police here is professional and cares for you as a visitor to ensure that you have a good experience in their country. In my view it’s the right thing to accept Police transfer invitations in some parts of Pakistan, also out of respect for the officers – when you transit fast through risky areas they have less work looking after you.

In Pakistan’s Balochistan province, in 2013 two Czech cyclists got taken hostage and in 2014 a convoy with a Spanish cyclist was attacked leaving six police officer dead. In 2013 there was also a terror attack in Nanga Parbat basecamp in which 10 climbers and one local guide got shot. There have been incidents in the larger region, for example in 2018 four cycle tourists got killed in Tajikistan.

Before my trip I spent extended time reading the “travel advice” websites of foreign offices from several countries. When you compare what the foreign offices of Germany/USA/UK etc. write, you can triangulate the current security situation pretty good.

The last police crew invited me for a tea and shared some great stories from their work, then they dropped me in Taxila which is about 30 kilometers northwest of Islamabad.

Last night I had searched for “campsite” on my offline map and found one marked inside the Rose and Jasmin Garden Islamabad. I couldn’t find a campsite there but a little restaurant where I sat at a bonfire with the owner and his friends for two evenings – they said I can just camp in the park behind the restaurant.

Already at Besham and also in Islamabad the nights were pretty foggy. I like the atmosphere the fog creates – it has something calm and peaceful, like a giant protective blanket covering everything and everyone.

The Rose and Jasmin Garden Islamabad is an oasis of tranquility and a great place to meditate. People go here for walks, families come here to play with their kids, and the park area is so large you can explore the nature for hours.

I explored Islamabad and got to know some locals – all very open-minded, funny, helpful, warm-hearted and overall amazing humans. They went the extra mile to make me feel welcome like an old friend and still today I feel grateful for their outstanding hospitality.

Shukriya! (thank you)

On the way out of Islamabad I stopped at the Adventure Foundation Pakistan which I had seen marked on a map while looking for outdoor stores – unfortunately nobody was around.

It’s an NGO focused on providing character development opportunities through outdoor activities:

“The mission of the Adventure Foundation Pakistan is outdoor education, a process of experience-based learning within natural settings. The outdoors and nature are teachers with infinite knowledge, it is up to the willing learner to absorb as much as they can.

The Urdu phrase in our logo “Kamil Insaan” broadly meaning “complete human” is a symbol of the perfectly balanced person in all respects: with themselves, the natural world and with others. This is the ideal our participants strive for. An ideal that can be aspired to even if not achieved. The aspirations and actions based on this ideal result in leading a life full of meaning and purpose.”

Kamil Insaan, a concept already discussed 1,000 years ago by Islamic scholars, centers on the development of self-awareness to unfold the human potential we all carry inside.

Philosophically deep, growth-oriented, pragmatic … definitely cool.

I left Islamabad and cycled into the night feeling inspired. I slept in a truck stop in Sarai Alamgir east of Jhelum River – “Sarai” in Urdu means “traveler resting place” and also here, just like anywhere in Pakistan, I received warm hospitality.

I got up early, drank a tea with my truck stop hosts, and starting cycling. I felt a lot of energy inside myself but a bit a lack of long-term direction.

Do you sometimes feel like that too? What do you do to reconnect with yourself and find the direction into which you want to live your life?

From Islamabad to Lahore I cycled on the N5 road which sometimes leads through the countryside and sometimes through city centers – cycling on this road is fun and easy.

I stopped to admire the elegance of a heard of water buffaloes. This domestic breed of the Punjab region called “Nili-Ravi” typically has a white marking on the forehead and is raised mainly for milk production.

The owner waved me over and invited me for a tea in his house at the center of the farm – every time I met Pakistanis my respect for their culture and values was growing.

With 250 million total inhabitants (2024), Pakistan is currently the world’s fifth largest country by population and growing fast – by 2050 Pakistan’s population is estimated to be 330-400 million humans. More than every third Pakistani is younger than 15 years making the population one of the youngest worldwide.

Punjab is Pakistan’s largest region and home to about half of the total population. From the road you see mostly agriculture but Punjab is also Pakistan’s most industrialized province.

I had thought I would cycle Islamabad-Lahore in three days (300 km) but ended up cycling it in two days as the cycling was such a nice flow – the trucks here drove just slightly faster than me which made blending into traffic easy.

A great experience on this road were the many locals who took the time to say hello – when I see these guys, I see that Pakistan has a good future.

I arrived in Lahore at night and checked into “Lahore Backpackers” in the northern city part. Here for the first time since Berlin I decided to take a longer break from cycling.

One factor was Khunjerab Pass. This 4,700 meter pass is the only land border crossing from China to Pakistan and around 1 December each year it closes due to snow until spring. The last months I had juggled route choices and cycling speed with this pass in mind as a “goal” before winter – but now south of the Himalayas there was no more bottleneck in time and place ahead on my tour, nothing external to achieve and focus on.

A second factor was the “Why?”. I left Berlin without a defined tour end in mind beyond “cycling to Asia” and now I felt it was time to take a good look again both on the map and inside myself.

Cycling east through India and then perhaps through Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam? Cycling south through India and then perhaps take a boat to Sri Lanka? Cycling generally for many more months or even years around the world?

Once on the road you don’t need much money when you mostly wildcamp and cook for yourself. But what about things like retirement savings and rebuilding a career? What about being a constructive tax-paying member of society and not just a very long-term cycling tourist? What about doing things for others?

A third factor was Pakistan. This country and the people here are amazing and I felt that I had just scratched the surface of this rich and diverse culture. I didn’t want to rush forward to be somewhere else – I wanted to explore and see more here in Pakistan because here I felt good.

So I parked the bike for a month and just lived. I explored Lahore – a city with 11 million inhabitants and many cool places to discover. I extended my tourist visa and explored more of Islamabad and Rawalpindi too.

And what I realized more and more with every additional day I spend here was the following: Pakistan means love for life.

Pakistanis care for details and do things with so much passion it touches you – people here are masters in living from the heart.

Pakistanis are happy to show you their life just like they are interested in your life – people here are warm and welcoming in a very authentic and beautiful way.

The 250 million Pakistanis are a pluralistic society and they know that thinking global while accepting diversity local makes their country strong – all people I met in Pakistan were tolerant and respectful of other people’s world views.

Pakistanis treat others with care and compassion – people here have a natural understanding that treating others well means treating yourself well as we are all connected.

Pakistanis are philosophers – people here have a high level of self-reflection regarding who they are and the values they live by.

The people’s love for life, their passion for being alive and living life well is reflected in many parts of Pakistan’s culture – for example in their trucks.

The Pakistani trucks make a bold statement and the statement is this: “Expressing artistic beauty is a priority for us no matter life’s challenges and we want to share our joy of life with you!“

Pakistani trucks are not something that can be bought of the shelves – each truck is unique and created with devotion. The paintings are made by hand, often including scenes of nature.

Most truck attachments are fabricated by hand too, for example thin metal plates which are first finely embossed and then painted over.

Released on the road, the trucks are an expression of joy – they bring beauty into the world.

Colorfulness, vitality, passion … you see it everywhere in Pakistan’s society.

You see it in the streets people buy clothes.

You see it in the streets people buy food, go to work, and live their everyday life.

You see it in the streets people buy decoration items and in the way they celebrate.

I’m happy to sleep in my tent in the mountains for months … but I must admit Pakistan’s cities are pretty cool places to explore.

Places that have seen empires come and go.

Places that have seen fighting and peace.

Places that make you dream.

And if you take a closer look inside those places you discover that they are full of life.

To some places people come for prayer.

To some places people come to find new perspectives.

To some places people come to spend time with their friends.

Pakistan’s nature has mountains and deserts and coast lines and wetlands – and is full of surprises. In Islamabad’s Margalla Hills live monkeys and leopards too … a magical place.

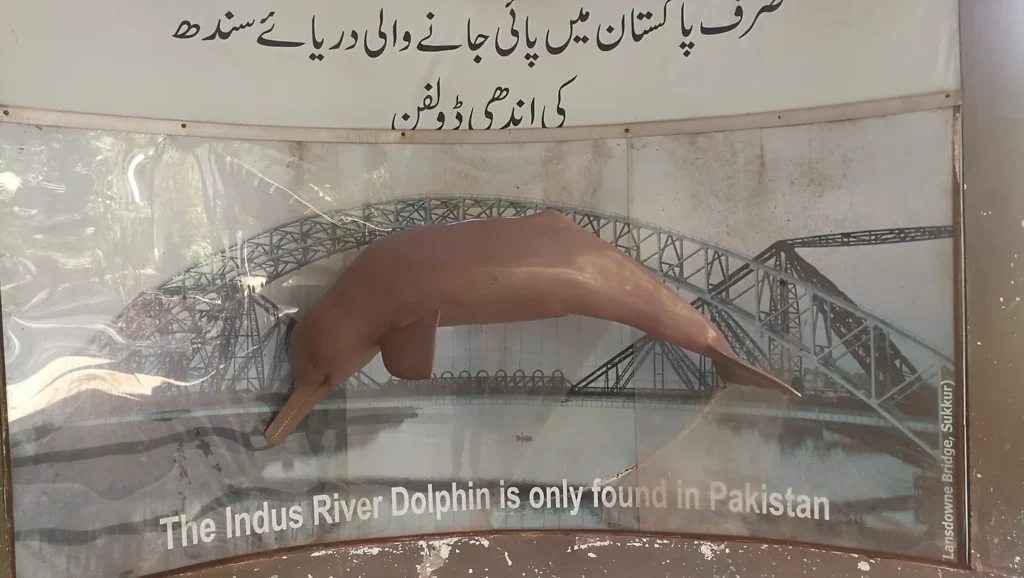

The Indus River Dolphin used to live in the entire Indus river system up to the foothills of the Himalayas. It struggles with new irrigation dams but due to successful conservation efforts the population has recovered to about 2,000 dolphins.

Pakistanis know how to cook delicious fried fish – large quantities are processed daily in the streets of Lahore.

Even in large cities you see animals regularly …

Animals transporting merchandise.

Animals transporting humans.

Animals transporting fascination … the lizard fat is used to produce an oil against erectile dysfunction while the snakes are just there for the show.

… and animals who are peacefully ignored.

When the night comes all that pulsating life in Pakistan’s cities continues and shows you another side.

Sometimes nights in Pakistan are bright and colorful.

Sometimes nights in Pakistan are peacefully dimmed and cozy.

And like in all countries and cultures of the world, the human-made spiritual places in Pakistan offer good meditation opportunities for consciousness exploration …

Sometimes it’s the colors making you think.

Sometimes it’s the sounds making you smile.

Sometimes it’s the humans going in and out making you feel.

And when you get hungry from all that exploration, Pakistan has you covered – the food here is good.

But the most amazing thing in Pakistan are the people. Beautiful people full of generosity and kindness and love for life – the values people cultivate here are an inspiration.

Pakistanis know well how to use their reality-bending force for the good … you can feel it whenever you spent time with them.

On my last day in Lahore while repairing a flat tire on the hostel rooftop I thought about the book idea that got me started on this whole trip.

Would I be able to write something meaningful on consciousness? Would anybody be interested in reading a book on consciousness? I had my doubts.

From Lahore to the border it’s just 30 kilometers – I cycled them slowly.

Wagah border is a border crossing in its own league. Since 1959 there is a daily border closing ceremony with border guards marching on both sides while hundreds of spectators cheer them on like in a football game.

I pushed my bike right through the middle of the spectators and waved back to the cheering crowd – I really liked that on both sides the people smiled.

At this place I had the feeling that the people living in Pakistan and India are brothers and sisters.

Pakistan, thanks for the joy of life. Perhaps it’s a good idea to remember that life is not about philosophy … and that feeling joy can bend reality pretty damn hard.