Bosnia and Herzegovina — Suffering

At noon I reached Bosnia and Herzegovina. There was a new border control infrastructure but with open gates and nobody around. Friendly first impression.

This morning in Metković I had spend my last 9 Croatian Kuna on 1 liter of gasoline which is about a week cooking. And with enough food for a couple of days in my bags, I had only made the plan to cycle up into the mountains and pick a route by feeling – what should go wrong?

Shortly after the border I passed Hutovo Plato – a major migration bird resting area with wetlands providing cover and nurture for hundreds of bird species migrating between Europe, Africa, and Asia.

I stopped at a mosque realizing that this was the first mosque I came by since leaving Berlin.

“How uneducated you are!”, I thought. Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country of my tour with Islam as the major religion and I didn’t even properly know the differences between Suuni and Shiite Muslims.

Knowing so little about other religions felt wrong and I was committed to changing this on my Silk Road tour – to leave all stereotypes behind and see for myself.

To soak in the local atmosphere, I rode on small streets and field paths for a while. Cycling here felt super authentic and I was happy I did it but some paths were pretty rough to cycle on.

Bosnia felt different from Croatia – more agricultural activities and generally more vegetation.

In the afternoon the temperature reached almost 30°C and the sun got so intense it was stinging on my skin.

While sitting in the shade for a break, a farmer stopped and sat with me in the grass for a while. He spoke some German – many people do in Bosnia. Germans have a good reputation here due to our help during and after the war. The farmer said that their politicians suck, but praised Angela Merkel.

The Bosnia war cost 100,000 humans their lives and more than 2 million people got displaced. Crimes against humanity were committed – prison camps, mass graves, systematic rape, murder of civilians, genocide.

The Bosnia war was just one conflict in a series of related wars triggered by the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia falling apart. Altogether an estimated 130,000-140,000 people died between 1991-2001.

Wars leave traumas and scars on people’s souls which can take generations to heal – you know that well when you grow up in Germany. I had the feeling the farmer enjoyed sitting with me in the grass as I, as a foreign cyclist, was a welcome sign of normality and peace.

Today the Bosnia war is still visible in many places in the country.

In Srebrenica alone, more than 8,000 civilians were massacred within days. This genocide got accurately documented: almost 90% of the dead got DNA-identified afterwards.

The Bosnia war brought large-scale killing back to Europe’s heart for the first time since the second world war. From Munich to Sarajevo it’s less than 1,000 km which you can drive with a standard car without a refueling stop.

What can you and I do to prevent wars from happening again?

Perhaps self-reflect more, integrate more our emotional biographies, and listening more to our feelings?

In Stolac I took a small road northeast following the Bregava river up into the mountains. I climbed for hours in the heat, no people around.

A sign “Ribolovni Revir” (fishing area) contained the note “Misli Mine!” (think mines). Land mines can be washed downstream hundreds of kilometers by rivers.

Politically the country Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of the two entities “Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina” and “Republika Srpska”. This division resulted from the Dayton Agreement in 1995 which aimed to stop the fighting.

About half way up from Stolac to the plateau I crossed into the entity Republika Srpska. Nobody around and there was an almost complete silence in the valley. I felt watched, but perhaps that was just my imagination.

Today I cycled through three different vegetation zones: the hot and humid lowland, the valley along the Bregava river, and the plateau. The valley and plateau felt untouched and mysterious, many items telling old stories and raising questions to the interested observer.

So there is war and suffering in this world. Now what?

Suffering. Hell. Evil. Socially constructed placeholder-words, all a bit dreamy in my view. But then again what else can we expect running up against the boundaries of language when verbally paraphrasing things beyond our limited human cognition?

Some say suffering is a fragmentary view thing. For example, one can believe in an all-loving pantheistic god and explain evil as a something relative to the observer’s perspective:

“The most popular model for dealing with evil is found in the philosophy of Spinoza who regards both error and evil as distortions that result from the fragmentary view of finite creatures; phenomena real enough to the finite beings who experience them but which would disappear in the widest and final vision of God. In this he was, of course, developing the Stoic sense that if we could see the world as God does, as the perfectly harmonious embodiment of the logos, we would recognize how its apparent defects in fact contribute to the goodness of the whole.“

Perhaps speaking in metaphors and parables is all we can do. Asked if he believed in god Albert Einstein replied:

“We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library, whose walls arc covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God.”

Others say suffering is a focus and attachment thing. According to this line of thinking, as long as we focus on worldly dharmas, for example by seeking pleasure and avoiding pain for ourself, we keep suffering. But by detaching our focus from ourself we can overcome suffering, for example by focusing instead on how we can be of service for others and the world.

And then others say suffering is a growth and development thing. Like when we develop strength and compassion and wisdom through practicing forgiveness, love, and healing the scars we have inflicted on each other’s soul.

I reached the plateau thirsty. I looked for a water source shown on my map but all I found was an overgrown ruin.

While searching for water I got a small cut which I took as a gentle reminder to be more present, to live more in the now.

Perhaps some things in life we only learn through suffering?

Should I walk over to the shepherd 100 meter off the road and ask him if he knows a water source in the area (they usually do) and then camp next to it? No, that would probably be a cool camp site but I wasn’t that thirsty and it was only 17:30 pm and I felt like exploring more.

Should I take a small side road left towards Hrgud or right towards Ljubinje? No, that would probably also be cool but I felt like cycling straight ahead.

Sometimes you just have to trust your feelings and go with the flow.

The first plateau is about 15 km by 3 km. A world in itself. The first town coming from Stolac is Berkovići which had belonged to Stolac’s municipality until the Bosnian war.

I asked for water in the only cafe in town and the owner happily filled my water bags. A couple of soldiers sitting in the back greeted me friendly.

Relaxed cycling enjoying the mountain panorama, zero traffic. I felt free, I felt myself.

The first plateau had a secluded and protected feel through the gently surrounding mountains.

The second plateau starts at Divin. The name makes sense, it’s the highest point of road.

I pitched camp on a spot overlooking the plateau. I felt grateful for this cycling day and the many impressions it had given me since starting in Croatia this morning.

Today I saw few people, mostly farmers living traditional lives, and some soldiers. Everyone here is smiling warm and shaking my hand. Thumbs up and friendly honks from drivers.

Just like the farmer who sat with me in the grass in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, also here in the Republika Srpska I’m sure people still have the war cruelties on their mind. And also here a foreign cyclist is probably a welcome sign of normality.

After dinner I lay in my sleeping bag and thought about Germany’s peaceful reunification after the Cold War. I felt a strong warm-hearted wish for everyone in Bosnia and Herzegovina to live with brotherhood, collaboration, and enduring peace.

Suffering seems to be a universal part of the human existence, something like a cosmic constant. Or does anyone never suffer?

We can reduce it, we can handle it with more grace. But in any case we all suffer throughout our lives – you and me too, dear reader.

Which types of suffering do we experience? What is “suffering” in the first place?

To keep things simple, let’s say there are two suffering types.

Physical suffering: When the artillery shrapnel shreds you legs and the bursting glass penetrates your eyes, you suffer. When you get raped the fifth time in 24 hours while you wait for the firing squad to send you to a mass grave together with your family, you suffer. When 70% of your skin is second-degree burned because you went back into your burning house to search a relative, you suffer.

Why those extreme examples? On the one hand, because they happen all the time in wars even so for you and me this kind of suffering may be far away. On the other hand, because sometimes physical suffering is reduced to “aging, sickness, and death” as natural body processes we can neatly transcend with meditation – when you are on the receiving side of a genocide you experience hell and philosophy is only helping you so much.

Emotional suffering: Painful emotions, such as hopelessness, fear, sadness, shame, and guilt. And perhaps worse: feeling disconnected, unloved, meaningless, and existentially alone.

We could discuss many specific suffering-examples like financial losses, discrimination, or hunger. But in the end the effect of all such things is, as far as suffering is concerned, that they either hurt you physically or emotionally.

Today I rode through a third plateau, this one covered with dense forest.

At the end of the plateau the forest disappeared and signs of human life came back.

The roofless houses in Bosnia and Herzegovina tell a story: 30 years after the war the scars of this country have not healed.

And even when new roofs are build, the traumas and scars on people’s souls may remain for a long time – until when?

In Germany, responsible for World War II and immeasurable suffering for the world, much has been written on war traumas being passed on across generations. And a central mechanism sociologists and psychologists agree on is that the lack of dialogue impedes healing. Offenders feeling too much guilt to speak, victims feeling to much pain to speak, and new generations often leaning towards simplified accusatory positions (“How could you …!”) instead of listening deep with empathy – difficult conditions to heal traumas.

Emotional healing is a process that sometimes works best in phases. For example, people suffering from severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often benefit from first going through a stabilization phase (e.g. learning relaxation techniques, re-learning to truly feeling safe), before going through a trauma confrontation- and integration phase. People have to be ready to face their toughest emotions for successful healing and integration.

What does this imply for our consciousness expedition?

The answer is individual as each emotional biography is unique. I think it generally implies that directly jumping to well-meant consciousness ingredients like “honesty”, “ownership”, and “acceptance” of traumas inside our consciousness may sometimes be too fast before stabilizing things like self-compassion are sufficiently developed inside us. But then again we have to face our pain at some point and not wait forever.

Where is the sweet spot? I would say we feel this individually inside our consciousness – and when we feel ready, we probably benefit from talking about our feelings with others.

I passed a farm with a cow shed. Outside, about 10 meters from the road, were two free guarding dogs with the physique of a lion – their cows must be save from wolves and bears as long as these dogs are around. I felt fear and respect and relief that they didn’t classify me as an intruder to their territory.

“Good dogs, I’m just cycling elsewhere minding my own business – just calmly going the other way, goodbye” … breathing in, breathing out.

Throughout the third plateau I saw many natural craters, some used by farmers to keep livestock it seems from the arranged stones around the crater edges. What formed those craters?

Probably rock dissolution resulting in sinkholes as karst limestone is common in this part of Bosnia which has funny topographical effects: The Huoto Plato nature reserve near the Croatian border is fed by a river flowing largely underground, and the Bregava river I cycled up to the plateau is a disappearing stream losing it’s water volume in the direction of flowing.

In Plana I stopped and studied my map. I knew I wanted to enter Albania from the north but how to cross Montenegro … should I cycle left towards Foča and cross Montenegro somewhere in the north, or should I cycle right towards Trebinje and cross central Montenegro somewhere via Niksic?

“Whatever, you don’t know how conditions are anyways”, I thought. The inner Balkan is simply too complex to predict from maps how things are like on the ground – the only thing you can count on is that you’ll definitely find mountains.

Today I felt like racing downhill so I turned right.

I reached the small town Bileća which had a spring feeling. Sometimes descending just 200-300 meter in elevation completely changes the climate you cycle in.

A party advertisement caught my attention. It was from the “Serbian Radical Party” (from the neighboring country Serbia) showing its founder and leader Vojislav Šešelj – a war criminal who spend nearly 12 years in a United Nations detention unit.

Vojislav got convicted by an International Criminal Tribunal for crimes against humanity given his role in instigating ethnic cleansing of the non-Serb populations in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Serbian Radical Party supports the idea of the creation of a “Greater Serbia” covering most countries of former Yugoslavia.

Bileća lake is a large artificial reservoir. It got created by the construction of the 123 meter tall Grančarevo Dam, which is the country’s tallest.

When the reservoir was built, medieval tombstones (Stećak) found in this area were moved to the reservoir’s northern shore. About 60,000 of such tombstones from the 12th-15th century have been found in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The tombstones show various elements from hunting scenes and astrological symbols to signs of the Bosnian, Catholic, and Orthodox church – creating them was common tradition. Some tombstones contain inscriptions in Cyrillic, Glagolitic, or Latin.

A famous tombstone found near Kočerin contains a long text in Bosnian Cyrillic ending with the words: “And please don’t step on me, I was what you are, and you will be what I am”.

Should I cycle left of Bileća lake and take the Deleuša-Vraćenovići border crossing this afternoon? Or right of Bileća lake and take the Klobuk-Ilino Brdo crossing tomorrow?

“Whatever, you don’t know how conditions are anyways”, I thought again. But going right meant cycling more elevation up, a higher border crossing point, and racing more downhill today – that felt like a good choice.

“Ok right, but for camping it would be smarter to stay high enough in the mountains instead of cycling down into Trebinje and arriving there at night”, I thought. But then again it would be nice to meet some locals and learn about their life.

“Fuck it, I just race down all the way into Trebinje center and see if I can make some friends!” – felt like a plan for the remaining day, and I started pedaling.

Trebinje has been a permanent settlement for at least 1,000 years. The city got shaken by power struggles and armed conflicts over the centuries – most recently it was a place of violence over ethnic and religious struggles during the Bosnia war.

As the southernmost city in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Trebinje has an interesting geographic location and climate: situated in the Trebišnjica river valley surrounded by mountains and close to the Adriatic coast results in a humid subtropical climate – lots of sunshine and rain in combination.

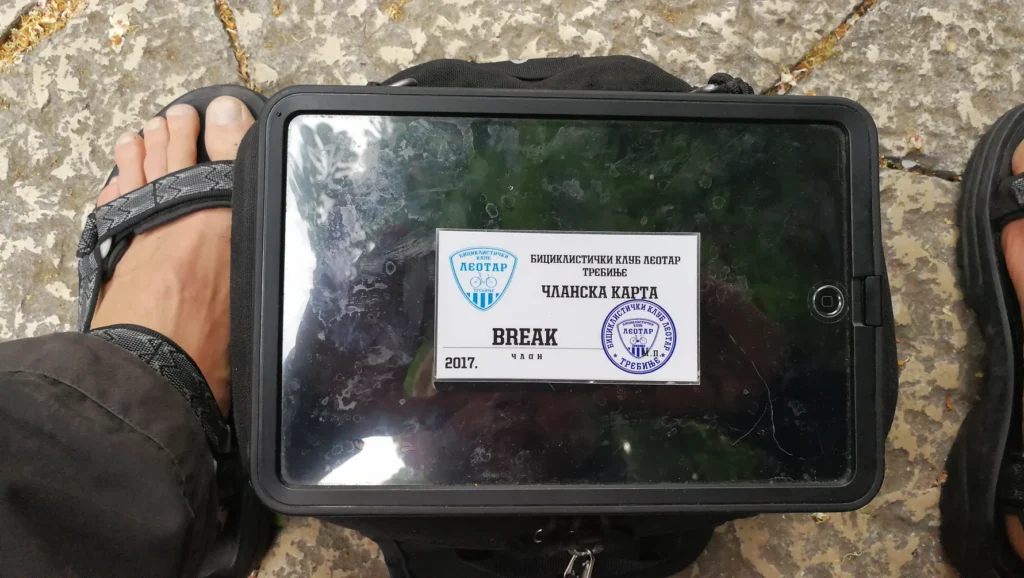

While cycling through the marvelous old town I got invited for a coffee by some gentlemen. It turned out they had just founded a new bicycle club and I was honored to quickly become member #15 of “Biciklistički klub Leotar“.

We chatted late into the night and I stayed with Rossi (second from left) who bikes every year 700 km from Trebinje to Greece in 5 days. Great guys, thanks a lot for everything – Hvala vam!

Bosnia and Herzegovina gave me a wet goodbye – but Trebinje gets 260 days of sunshine and also with rain the city has a welcoming, vibrant, and mediterranean feel.

I left Trebinje at noon and cycled towards the border with Montenegro. I rode in rain gear all day, climbing from about 300 meter to 1,000 meter elevation.

First I followed the Trebišnjica river east which comes down from the highlands. It’s another disappearing stream losing it’s water volume in the direction of flowing. The river system also sinks under ground and rises again above it several times from the mountains to the coast, making the Trebišnjica one of the longest sinking rivers of the world.

In Jazina I left the river and cycled up some sharp serpentine towards the border pass. Zero traffic on the road, zero people around, peaceful and meditative cycling.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, I wish everyone in this fantastic country that the war scars on people’s souls heal.

People here can be proud how they carry their suffering and keep moving forward … it’s an inspiration for consciousness exploration (I guess we all encounter suffering, one way or another).