Uzbekistan — Thankfulness

The Uzbekistan border crossing went surprisingly smooth – from online reports I had expected lengthy checks but there were construction works in the customs building and I had the feeling the staff had better things to do than searching my belongings.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 Uzbekistan was governed by the quasi dictator Karimov – famous for brutal repression, secrecy, paranoia, forced labor, and torture. But in 2016 he passed away and 25 years of isolation and leadership by brutality ended.

His successor started an ambitious economic modernization and structural reform program, abolished forced labor, closed prison camps, reduced corruption, and let foreign journalists into the country – I hadn’t followed the modernization developments before coming to Uzbekistan but in retrospect I experienced so much positivity here that it all made sense.

I stopped at the first road sign in Uzbekistan. It didn’t mention Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent (or in fact any city in Uzbekistan) but rather Dushanbe (Tajikistan), Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan) and Almaty (Kazakhstan) – perhaps this sign was made with long-distance truck drivers in mind? But then again the first intersection after the border was still 20 km ahead so the sign can’t be about taking a right turn. In any case the sign had a beautiful light blue.

I just ate a snack this morning but now it was time to cook a proper breakfast while using the opportunity to sit in the shade – Uzbekistan is as hot as Turkmenistan.

Another beautiful road sign … if only our inner consciousness journey was that easy, right? Like having one direction to follow instead of the multi-layered complexity of our feelings and thoughts and choices and overall life experiences.

But perhaps with a bit of practice and attention we can also align our reality-bending force with a single direction perceivable in the beautiful multi-dimensional complexity of life.

Isn’t that what we all already do when we “follow the direction that feels right”?

Today I cycled slowly with frequent breaks to let the impressions of the new country sink in. On the bike I definitely love racing, but sometimes just randomly stopping in the middle of nowhere and sitting next to the road and thinking about nothing is when travelling feels best.

Perhaps we arrive at a deeper understanding of our life when we stop looking for anything in particular, when we spent time in a non-cognition focused consciousness state, just letting our feelings arise as they are.

I stopped in a little shop and changed some dollars with the friendly owner. She was about 50, looked like a mother, looked like someone who has learned to handle life’s challenges with confidence and a smile.

In the evening I reached Bukhara and checked into the hostel “Rumi” – named after a 13th century Persian poet who wrote:

“While outward travelling lies in words and deeds

Beyond the sky the inner journey leads”

I stayed in hostel Rumi for five nights and mostly relaxed – the desert cycling stretch since Mashhad had been intense.

I glued and sewed some of my equipment and also managed to fix my saddle with a rusty screw that I got from the hostel manager.

On the last evening I did some sightseeing by bike. Bukhara is more than 2500 years old making it one of the oldest Central Asian cities. Within the “Silk Road”, which has always been a network of roads connecting Asia and Europe, Bukhara lays roughly in the middle.

Silk Road travelers 2500 years ago, you and me today, every other human across time – we all make an inner journey over the course of our lifetime. But what exactly happens in our consciousness?

I believe there are two equally valid answers.

On the one side, each inner journey is unique – you are the only person in the history of the universe who ever lives your individual version of a human life.

On the other side, all our life paths are structurally the same – we get born, age, and die. And along this external structure our inner journeys seem to have similarities, such as the evolvement of our consciousness attention from the surface to the deep.

What do you think about our inner journey, dear reader?

There are many different route variants and touring styles cycling from Europe to Asia. Riding flat or hilly terrain? Tarmac or backcountry roads? Hotels or wildcamping?

These questions need to be considered in combination with the equipment brought, the macro route choices, and the time of the year – it’s all a matter of personal touring preferences.

Whether you cycle north or south of the Caspian Sea, you can plan an entirely flat route from Europe to Asia, or search elevation – cycling, like life in general, is not a competition and in my view it doesn’t really matter which external path we choose as long as it feels right.

Personally, in Bukhara I had a long look at a geographical map of Central Asia and decided to simply stick with my route principle of always riding the higher route in all countries if given alternatives – this touring style felt right.

For my route forward this meant cycling a line through a region whose name will resonate like thunder in the chest of any mountain-committed touring cyclist: Pamir.

Why does the sun shine in my face at noon when I cycle east? That thought should have occurred to me earlier as I had missed a turn which added one cycling hour to this day – but then again “wrong” or “right” on the external path don’t exist when the inner journey is the goal.

Unexpected detours often make for the best encounters anyways – in the evening a very drunk and friendly gentleman chatted me up on the street and I ended up staying with his neighbor.

They proudly presented me their cows – many families here raise cows in their backyard and sell the meat. To show me some action we went to a friend who was butchering a cow.

The butcher room featured a hole in the middle of the floor to collect the blood, and a metal ring cemented next to it to force the cow’s head down with a rope. The disjointing technique looked skillful and all cow parts were used.

I was deeply touched but the hospitality and trust I received. The family let me sleep in the middle of their home and we ate dinner and breakfast together – I came as a sweaty stranger and left as a friend.

The family kept a nightingale who started to sing beautifully in the morning around 5am. Have you ever heard one?

Nightingales, the national bird of Iran, know over 200 verses of tweeting and singing which they creatively combine into an acoustic experience that is unpredictable, and magic … just like our inner journey.

I followed the Zeravshan river valley to the east. Easy cycling conditions, very friendly and open people.

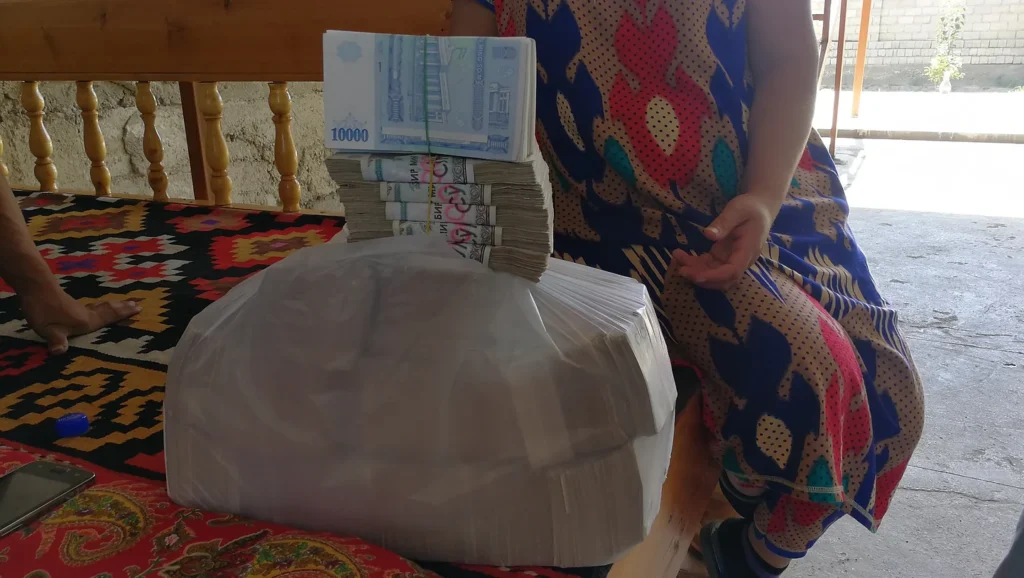

A shop owner invited me to eat lunch with him and his wife at their home. They had just packed a large plastic bag with their monthly earnings to be sent to their bank in Tashkent – Uzbekistan has seen a sporty inflation for a while.

But since 2017 Uzbekistan has worked hard and consistent on reforms – and with success.

When Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, visited Uzbekistan in 2019 she praised Uzbekistan’s work to stabilize prices and combat corruption:

“As President Mirziyoyev said at the United Nations last year, new digital tools can and should help restore trust in government. He is making good on that promise. Last year, the President’s online town hall site received over 2,000,000 questions. So clearly there is an interest. Many are taking notice. This goes to show how Uzbekistan can be a model for others, and how the work done here can be a force multiplier for good throughout Central Asia.”

This praise is shared by others. For example, the newspaper Economist voted Uzbekistan as the country that improved the most worldwide in 2019, and in 2022 the Brookings Institution found that “impressively” Uzbekistan’s reform momentum was not slowed by the coronavirus period.

Perhaps there is something like a pendulum in societies and after dark times of dictatorships and brutality and wars, it swings towards the good.

Is this pendulum perhaps swinging in the chest of people?

The positivity of the people in Uzbekistan gave me momentum and today I cycled effortlessly 160 km. It got already dark when I looked for a campspot east of Kattakurgan where a restaurant owner invited me to stay with him for the night.

He was farming carps in a pond and specialized in serving fresh fish – when people ordered fish he caught them with a landing net. Guests were sitting on comfortable elevated platforms in the shade of densely planted trees watered by small irrigation channels.

The restaurant owner told me about the local history but my Russian wasn’t good enough to understand the details. He first offered me to sleep on the platform but when late in the evening drunk guests were passionately telling me stories for hours (“I was a sniper in Kazakhstan and today I work for Uzbek railways …“) he invited me to sleep in his house nearby.

The next morning he went to get fresh bread and eggs for me and when I left he wouldn’t accept any money I tried to give him. He and his family radiated an unconditional warm kindness and generosity that was touching.

From Kattakurgan I cycled southeast towards Samarkand. A farmer on the roadside gave me a large watermelon as a present and I cycled with it all day to share it with others in the evening.

The five Central Asian countries Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have a combined population of about 70 million, and half of those people live in Uzbekistan.

This doesn’t mean that Uzbekistan is densely populated outside cities – the other countries are just even less populated. Kazakhstan is six times as large as Uzbekistan in square kilometers but has only half the population.

But the stretch between Bukhara and Samarkand along the Zeravshan river is full of agricultural cultivation and traffic – today I was looking forward to the emptiness of the desert ahead.

I reached Samarkand and checked into a downtown hostel. As a Soviet era legacy, Uzbekistan required foreigners to register every third night so I couldn’t wildcamp or stay with locals all the time – and the paper registration slips were checked at the border exit crossing with potential fines for incompleteness.

Meanwhile you can sleep wherever you want and do the registration yourself online.

In the morning I organized my Tajikistan e-Visa and GBAO-permit for the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (a region in Tajikistan’s east). It took me several hours to get the payment through a VPN app, upload my passport picture in the right file size, and refresh the crashing website about 50 times given the slow internet speed, but in the end it all worked out fine and I could print my e-Visa in a kiosk.

Great that this works online Tajikistan – thank you very much!

Next I explored Samarkand by bike:

Samarkand has stories to tell – when the Greek king Alexander the Great conquered this city 2300 years ago, Samarkand had already been around for at least 400 years.

The rare occasion of cycling around without bike bags always feels like being superman: the muscle memory applies the same force used to propel the loaded touring bike which makes you effortlessly speed down the roads like a rocket – this is fun!

Cycling makes thirsty – time to discover a local drink:

Back in the hostel I cleaned my drivetrain and changed my chain – I couldn’t have possibly done it without a new friend I made in the hostel who was eager to help me.

Samarkand felt like a city raising up – sure, only the center is polished and the outskirts are rather poor, but overall this place seemed to have a lot of forward momentum.

Keep going guys! … I wished this city and its inhabitants the best.

Headwind cycling south of Samarkand – it felt good to ride into the mountains again.

At the pass separating the Samarkand from the Qashqadaryo region I stopped at a monument. Today’s elevation profile was straightforward – constant uphill until here, constant downhill for nearly the rest of the day.

This side of the mountain chain was much dryer than the Samarkand side – I liked the Qashqadaryo region from the beginning.

While racing downhill my fuel bottle got detached and almost rolled over a cliff – potholes on the road shake the bike and equipment much more than when cycling over smooth tarmac.

I cycled long into the night and ended up making it a 140 km day despite the pass – cycling in the desert after sunset feels special.

The desert is a place where our outer path and inner journey are free of distractions, a place allowing our consciousness meditation to become deep – a calm environment were we feel more.

The French pilot and writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes in the book “The Little Prince” about the desert:

“I looked across the ridges of sand that were stretched out before us in the moonlight. ‘The desert is beautiful,’ the little prince added.

And that was true. I have always loved the desert. One sits down on a desert sand dune, sees nothing, hears nothing. Yet through the silence something throbs, and gleams …

‘What makes the desert beautiful,’ said the little prince, ‘is that somewhere it hides a well … ”

Do you feel this well? You can experience it anywhere you are.

I’m just a cyclist and I don’t know much about spirituality. Also, I believe that if there are things larger than our cognition can grasp, everyone senses them differently and when we try to speak about them we use individually unique metaphors – your world conception is as correct and valuable as mine.

So regarding thankfulness I think it’s up to everbody individually to link this to spirituality or not. Personally, I lean towards explanations and concepts that resonate inside my consciousness – but I respect that everyone is different.

However, I think thankfulness is something powerful and healing in many non-spiritual contexts in our daily life – this I believe we all share.

Like “being thankful for what I have”. Like “being thankful for my breathing body”. Like “being thankful for being a part of nature”.

Breathing in, breathing out.

In Guzar a got a roadside coffee (0.1 Euro) and restocked water – time to hit the road.

Today’s elevation profile was simple: uphill all day to a pass separating the Qashqadaryo and Surxondaryo region.

Pretty calm area, almost no traffic.

Today was a great day for cycling meditation – even in the few settlements I passed there were basically no distractions.

In the afternoon I met some gentlemen drinking at a roadside restaurant. One of them had served as a Soviet soldier in Naumburg, East Germany and still spoke some German: “Halt, links gehen! Halt, rechts gehen! Halt oder ich schieße!” (Stop, walk left! Stop, walk right! Stop or I shoot!).

Another bike tourer I knew from Iran coincidentally came by. We cycled together until I had flat number five since Berlin – a thorn. My cycling fellow had two flat tires by thorns that day so perhaps there was a particularly thorny plant growing in this region given the statistical cluster.

The higher I cycled the worse the road became. Pretty common effect for a pass.

I pushed my bike over the pass as the last part was too steep to cycle.

After the pass a perfectly new tarmac was an invitation to race downhill – I accepted.

I caught up with my cycling fellow at a military checkpoint where we had to do a quick registration. From here the main road leads into Afghanistan in the south, but we took a small road to the east towards Tajikistan.

The downhill after the checkpoint was relaxed but then we climbed for two hours over another pass up to Baysun – second consecutive day of night cycling.

Just 140 km cycled, just 2200 meter cumulative uphill, but given the heat, road condition and long day, today was one of the toughest days of my tour.

Today was a long day in the saddle but of course the longest journey we all make is inside.

Do you think our lifetime is enough to find out who we are?

You really exist, you are not just a “mental concept” of yourself. You are very much a biological being alive and breathing right now – feel your pulse at your wrist.

So what will you do between today and the day your pulse stops?

I’m just a cyclist but I would say do what you want, do whatever feels right to you. If paying attention to your consciousness and inner journey feels right, do it. It’s free and you can do it in any situation of your life.

And while simplifications about causalities between “things” in our consciousness need to be made carefully given the multi-layered complexity of our consciousness and the reality we exist in, I believe one relationship to be generally true: feeling thankfulness and living deeper go hand in hand.

When we practice being thankful for what we have in our daily life (the miracle of our eyes? our breathing lungs? …), our consciousness perception becomes deeper. And the other way round, when we practice letting our consciousness expand, we somehow naturally develop, or find, more thankfulness inside.

Breathing in, breathing out.

East of Baysun we passed a monument on Amir Temur – a Turco-Mongol conqueror born in this region who in the 14th century build an empire stretching from Aleppo to Delhi.

Temur’s army was multi-ethnic and consisted of troops from different nations, each with their specialization – in humanity’s history, multi-national collaboration and unity-in-diversity have often been key ingredients for long-term success.

21st century + humanity: what would happen when we feel each other more, and we align our individual reality-bending forces to a joint reality-bending force?

What would?

If a cyclist cycles down a road and nobody seems him, does he exist?

If a road exists and nobody sees it, does it exist?

Breathing in, breathing out.

Reality is a good place to sometimes just exist and have fun.

In the afternoon we reached the Surkhandarya river valley, followed it north, and checked into a hotel close to the border.

I really like cycle touring – cycle touring is my friend.

Uzbekistan, your brave people endured a brutal dictatorship and isolation for decades … but now you radiate so much positive momentum it’s inspirational. The Uzbeks have my respect – thank you for the ride.